“This webinar has a long and intricate title ‘Practical implementation of the three non-legally binding IHRA working definitions in multicultural societies’, but, for once, a long and intricate title does not do justice to the importance and depth of what we are about to undertake. Even more, the importance of our task works on two levels: the first being that of the actual issue at hand, combating Antisemitism, anti-Roma discrimination and other forms of prejudice while, at the same time, holding a major scientific and very much political event , involving some of the finest minds in the field in South East Europe.

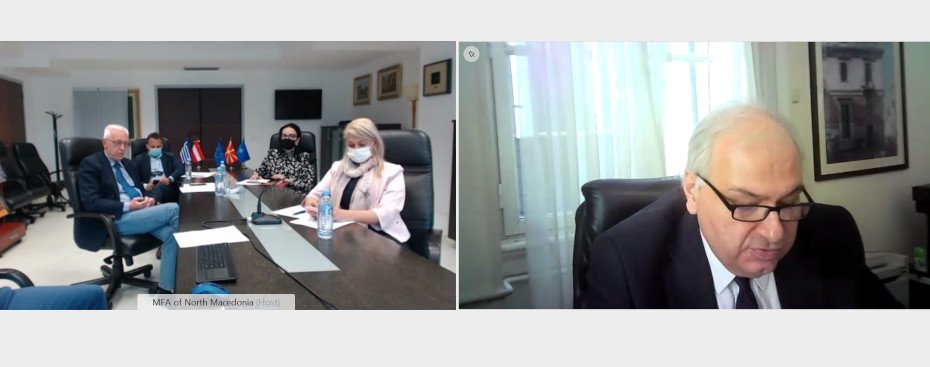

Kudos have to go to the organizers and prime movers of this webinar, Ambassador Jovan Tegovski and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of North Macedonia, as well as Ambassador Thomas Michael Baier and the Austrian federal authorities involved in this project. May I also thank the Presidency’s own partners in Greece, the Ministry of Education, in particular Secretary General George Kalantzis and Director Vassiliki Keramida, who had been into it, long before the Greek Presidency of the IHRA had started.

Incorporating the IHRA’ working definitions into the legal environment of various countries has proved an undertaking requiring a very careful, sensitive, and at the same time cool scientific approach. While the content and language of the Working Definitions was one, legal environments varied: in other words, it was not the new content but the pre-existing local background, or even the underlying legal mentality that often required adaptation. This effort has been concluded successfully in many countries and the IHRA’ working definitions are already part of their legal armoury in the fight against Antisemitism, denial and distortion of the Holocaust and anti-Roma discrimination.

On the other hand, discrimination means, in practical terms, helping audiences at large understand and interiorize the concept of the problem, as well as mobilizing them to search and apply solutions: This is not a process that can be brought to fruition in a short period of time.

This is where education and educators come in. Their task is, first, to keep alive the memory of the events on which this effort is based, i.e. the Holocauste and the widespread atrocities of the Nazis and their ilk, to pass it onto the newer generations, all the while adapting our methods to the ever evolving conditions of the ideological battlefield. Just a few decades ago, when memories were still fresh, few would dare express nostalgia for extremist ideologies; now, economic and other difficulties aiding, there is a resurgence of such phenomena.

In South East Europe, where Nazi rule proved particularly harsh, towards both Jews and Gentiles, and where memories tend to be tenacious, there was for decades an informal, but widespread consensus condemning their atrocities, or, then, an eerie silence upon the matter. Upheaval in many parts of the region, since the 1990’s and, more recently, doubts about our societies’ well-being and their place in the European construct, permitted extremist voices to surface, combining far out, but bloody-eyed ideas, with abject ignorance.

Ignorance, misinterpretation and misinformation –I like the French word for it, intoxication, for the thing is toxic– are the enemy today; this is the battlefield educators are called to take up their fight, not only in the classroom, but also in real day-to-day life and, increasingly, nowadays, in the digital world.

Thank you for your patience and attention.”